Pleural Effusion: Causes, Thoracentesis, and How to Prevent Recurrence

Jan, 31 2026

Jan, 31 2026

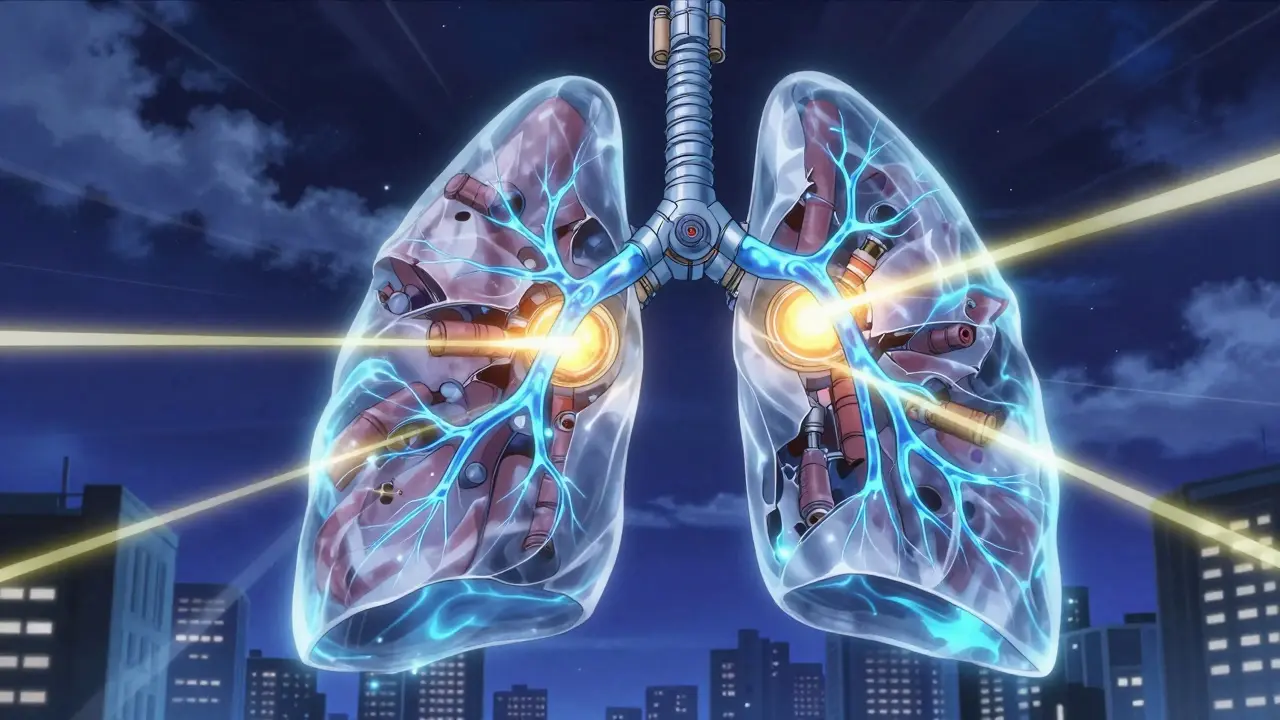

What Is Pleural Effusion?

When fluid builds up between the layers of tissue lining your lungs and chest wall, that’s called a pleural effusion. It’s not a disease on its own-it’s a sign something else is wrong. Think of it like water pooling in the space around your lungs. That extra fluid pushes on your lungs, making it harder to breathe. You might feel short of breath, especially when lying down or moving. Some people get a sharp chest pain when they inhale, or a dry cough. Others feel fine until a routine X-ray shows the fluid.

About 1.5 million people in the U.S. get this each year. The most common cause? Heart failure. It accounts for half of all cases. But other causes include pneumonia, cancer, liver disease, and even blood clots in the lungs. The key is figuring out why the fluid is there-not just removing it.

Transudative vs. Exudative: The Two Main Types

Pleural effusions are split into two main types: transudative and exudative. This isn’t just medical jargon-it changes everything about how you treat it.

Transudative effusions happen when fluid leaks through healthy blood vessels because of pressure changes or low protein levels. The most common cause is heart failure. When the heart can’t pump well, pressure builds up in the blood vessels near the lungs, forcing fluid out. Liver cirrhosis and severe kidney disease (nephrotic syndrome) can also cause this type. The fluid here is usually clear and low in protein.

Exudative effusions are more serious. They happen when the lining around the lungs gets inflamed or damaged. This lets protein, cells, and even bacteria leak into the space. Pneumonia is the biggest culprit-responsible for nearly half of all exudative cases. Cancer is next, causing 25-30%. Pulmonary embolism, tuberculosis, and autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis can also trigger this type. The fluid is thicker, richer in protein and cells, and often signals a more urgent problem.

Doctors use Light’s criteria to tell them apart. It’s a simple test comparing protein and LDH levels in the pleural fluid and blood. If any one of three numbers is out of range, it’s exudative. This test is 99.5% accurate. Getting it right matters because treating a cancer-related effusion like heart failure will do nothing-and delay life-saving care.

Thoracentesis: The Procedure to Drain the Fluid

If the fluid is more than 10mm thick on an ultrasound, or if you’re struggling to breathe, doctors will likely do a thoracentesis. This is a simple but critical procedure where a thin needle or catheter is inserted between your ribs to drain the fluid.

It’s done under ultrasound guidance now-no exceptions. Before ultrasound became standard, complications like collapsed lungs (pneumothorax) happened in nearly 19% of cases. Today, that’s down to just 4%. Ultrasound shows exactly where to stick the needle, avoiding the lung and blood vessels. It’s not optional anymore. It’s the rule.

The needle goes in between the 5th and 7th ribs on your side, near your armpit. You’ll sit forward, leaning on a table. The area is numbed. You might feel pressure, but not sharp pain. For diagnosis, they take 50-100 mL. For relief, they can remove up to 1,500 mL in one go. Removing too much too fast can cause re-expansion pulmonary edema-a rare but dangerous swelling of the lung. That’s why doctors monitor you closely afterward.

The fluid gets tested for: protein, LDH, cell count, pH, glucose, and cancer cells. A low pH (below 7.2) or low glucose (under 60 mg/dL) often means infection or empyema. High LDH (over 1,000 IU/L) raises red flags for cancer. Cytology finds cancer cells in about 60% of malignant cases. Sometimes, they’ll check amylase if pancreatitis is suspected, or hematocrit if a blood clot might be involved.

What Happens After Thoracentesis?

Draining the fluid helps you breathe better right away. But if you don’t fix the root cause, the fluid comes back. That’s why the real work starts after the needle comes out.

For heart failure patients, the goal is to get the heart working better. Diuretics like furosemide are the first line. When doctors use NT-pro-BNP blood tests to guide treatment, recurrence drops from 40% to under 15% in three months. ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers help too. No need for repeated drains if the heart is managed well.

For pneumonia-related effusions, antibiotics are essential. But if the fluid is thick, infected, or has a pH below 7.2, it won’t clear with antibiotics alone. That’s when drainage becomes urgent. Left untreated, 30-40% of these turn into empyema-a pus-filled pocket that can require surgery.

Malignant effusions are the trickiest. Without treatment, half of them return within 30 days after just one drain. That’s why doctors don’t stop at thoracentesis. They move quickly to prevent recurrence.

Preventing Recurrence: What Works

Stopping fluid from coming back depends entirely on what caused it in the first place.

For cancer-related effusions: The two main options are pleurodesis and indwelling pleural catheters. Pleurodesis means sealing the space shut. Talc (a mineral powder) is injected through a chest tube. It irritates the lining, causing it to stick together. Success rates are 70-90%. But it’s painful-60-80% of patients report moderate to severe pain. Hospital stays average 5-7 days.

Indwelling pleural catheters are changing the game. These are small tubes left in place for weeks. You or a caregiver can drain the fluid at home, usually once or twice a week. Success rates? 85-90% over six months. Patients go home the same day. Hospital stays drop from over a week to just 2 days. Many patients prefer this because they keep control and avoid major surgery.

For heart failure: Keep the heart strong. Stick to meds. Watch your salt. Monitor weight daily. If fluid builds up again, it’s a signal your treatment needs tweaking-not another drain.

For parapneumonic effusions: Drain early if pH is low or glucose is low. Don’t wait. Delaying drainage increases the chance of needing surgery by 30-40%.

After heart surgery: About 1 in 5 patients get fluid. Most clear on their own. But if more than 500 mL drains per day for three days straight, doctors will keep a chest tube in longer. This prevents recurrence in 95% of cases.

What Doesn’t Work

Not every pleural effusion needs treatment. Small, silent effusions-especially in people with no symptoms-often don’t need a thoracentesis. A 2019 JAMA study found that 30% of procedures done on asymptomatic patients added no value. They didn’t change diagnosis or outcome. That’s unnecessary risk.

Also, don’t use chemical pleurodesis for non-cancer cases. The American Thoracic Society says there’s no proof it helps for heart failure, liver disease, or kidney-related effusions. It just causes pain and complications with no benefit.

What’s New in 2026

Recent advances are making management smarter and gentler. One big shift: pleural manometry. During thoracentesis, doctors now measure pressure inside the chest. If it drops below 15 cm H2O, you’re safe to drain more fluid without risking lung swelling. This lets them drain more completely, safely.

Another trend: personalized care. Not all cancers are the same. Lung cancer, breast cancer, and lymphoma respond differently to treatment. Tailoring therapy to the cancer type and the patient’s overall health has cut recurrence rates for malignant effusions from 50% to just 15% in recent studies.

And survival? It’s improving. Five years ago, only 10% of people with malignant pleural effusion lived five years. Now, it’s 25%. Better cancer drugs, earlier detection, and smarter drainage techniques are making a real difference.

Bottom Line

Pleural effusion isn’t something you just drain and forget. It’s a symptom. And like any symptom, it’s pointing to something deeper. The goal isn’t just to make you feel better today-it’s to stop it from coming back by fixing what’s causing it.

Ultrasound-guided thoracentesis is now standard. Light’s criteria are non-negotiable for diagnosis. For cancer, indwelling catheters are often better than talc. For heart failure, meds work better than drains. And for pneumonia, don’t wait-drain early if the fluid looks infected.

Ignoring the cause is like bailing water from a sinking boat without fixing the hole. The best treatment always starts with asking: Why is this happening?

What are the most common causes of pleural effusion?

The most common cause is congestive heart failure, responsible for about half of all cases. Among exudative effusions, pneumonia is the leading cause (40-50%), followed by cancer (25-30%), pulmonary embolism (5-10%), and tuberculosis (5%). Other causes include liver cirrhosis, kidney disease, and autoimmune conditions.

Is thoracentesis painful?

The procedure itself isn’t usually painful. The area is numbed with local anesthetic, so you’ll feel pressure but not sharp pain. Some people feel a brief tug or discomfort when fluid is drained. Afterward, mild soreness at the insertion site is common. Serious pain is rare unless complications like pneumothorax occur.

Can pleural effusion come back after drainage?

Yes, especially if the underlying cause isn’t treated. For malignant effusions, about 50% return within 30 days after a single drainage. For heart failure-related effusions, recurrence drops to under 15% with proper medication. The key is treating the root cause-not just removing the fluid.

What’s the difference between pleurodesis and an indwelling pleural catheter?

Pleurodesis uses a chemical (like talc) to seal the pleural space so fluid can’t collect again. It’s a one-time procedure but often requires hospitalization and causes significant pain. An indwelling pleural catheter is a small tube left in place for weeks. You drain fluid at home as needed. It’s less invasive, allows quicker recovery, and has higher long-term success for recurrent malignant effusions.

When is pleural effusion an emergency?

It becomes urgent if you have sudden severe shortness of breath, chest pain, fever, or signs of infection like rapid heart rate or confusion. If fluid is infected (pH <7.2, glucose <40 mg/dL, or positive Gram stain), it can turn into empyema-a life-threatening pus collection. Prompt drainage is critical in these cases.

Do I need to stay in the hospital after thoracentesis?

Not always. For simple diagnostic drains, you can often go home the same day. If you’re getting a large volume drained or have other health issues, you might be monitored for a few hours. For pleurodesis or indwelling catheter placement, a short hospital stay is typical. But with catheters, many patients are discharged within 24 hours.

Chris & Kara Cutler

February 2, 2026 AT 03:21Donna Macaranas

February 2, 2026 AT 15:26Rachel Liew

February 2, 2026 AT 17:35Lisa Rodriguez

February 4, 2026 AT 08:27Also indwelling catheters are a game changer. My uncle’s been using one for 8 months and he’s fishing on weekends like nothing happened

Lilliana Lowe

February 5, 2026 AT 10:07vivian papadatu

February 6, 2026 AT 10:30Melissa Melville

February 7, 2026 AT 07:42Naresh L

February 7, 2026 AT 08:56Sami Sahil

February 9, 2026 AT 08:42franklin hillary

February 9, 2026 AT 22:38Bob Cohen

February 11, 2026 AT 18:09June Richards

February 12, 2026 AT 04:50Jaden Green

February 13, 2026 AT 01:55Lu Gao

February 14, 2026 AT 17:55Angel Fitzpatrick

February 15, 2026 AT 02:41